The Porch, and Other Impossible Originals, RO / IT: A Temporary Installation

Proposal for the Romanian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale / 2025

Radu Remus Macovei of StuffStudio collaboration with co-authors Alexandru Vilcu, Zsuzsa Peter, Denisa Balaj, Edward Wang

Apart from the big letters ‘R-O-M-A-N-I-A’, there is little else to identify the Romanian pavilion within the grounds of the Giardini. Part of a larger ensemble accommodating ‘new nations’ planned and built by Brenno del Giudice in 1938, the building is imbued with the political, aesthetic, and physical traits affiliated with European modernism of the 1930s: stability, monumentality, and permanence. A kind of charged blank, the pavilion stands witness to the tides of the contemporary Biennale context, where installations arrive and vanish in fleeting succession. Every six months, after its contents and the statements they carry are cleared, the pavilion is yet again patched, plastered, white-washed back to its former immaculacy.

From the example of the pavilion—the monumental shell and its ever-changing interior—we might extract a generalisation about architecture: the desire for the durability and solidity of its image is often in tension with the realities of its purpose, which must be attuned for adaptation and change. Our proposal challenges this binary by introducing the notion of sempiternity. The sempiternal describes that which exists within time yet endures through perpetual transformation. Neither eternal nor fully ephemeral, a sempiternal architecture implies the longevity of architectural assemblages with tectonic features that maintain it in a malleable state, perpetually changing. Semiternity is a determining feature of Romanian architecture’s stubborn other – what might be termed vernacular or local intelligence. Buildings made from wood to clay, covered in shingles, tiles and hay, transform over time to adapt to changing conditions, from demographic growth and shrinkage (the addition or removal of rooms) to economic needs (the sale or purchase of buildings, parts, or materials) to aesthetic adaptations (e.g. the replacement of spires with bulbous domes in wooden churches and vice-versa). Shifting away from the Vitruvian assumption of firmitas that biases masonry and permanence as preconditions for ‘building-as-architecture,’ these practices demonstrate an understanding of buildings as transformable assemblages.

Amidst larger discourses surrounding circularity, the temporal mode through which architecture is produced and sustained has become increasingly up for debate. The sempiternal assemblage, as a rhetorical frame for architecture, liberates us from the need to find and freeze the ‘original’, and spares us from exhausting any potentially dangerous associations of the ‘authentic’. By now, preservation for the sake of preservation is well trodden territory; by turning away from the crisis of the original, we hope to offer to Biennale attendees and visitors to the ICR Gallery an insight into how Romanian architecture adapts, renews, and ultimately endures through actions within the everyday.

A LOCAL SOLUTION:

Responding to Carlo Ratti’s prompt "One Place, One Solution," we adopt an approach that is both pragmatic and layered: our place, the Romanian pavilion itself, recast as an architectural site; rather than one solution, a polyphony of stories of adaptability and transformation within Romanian architecture.

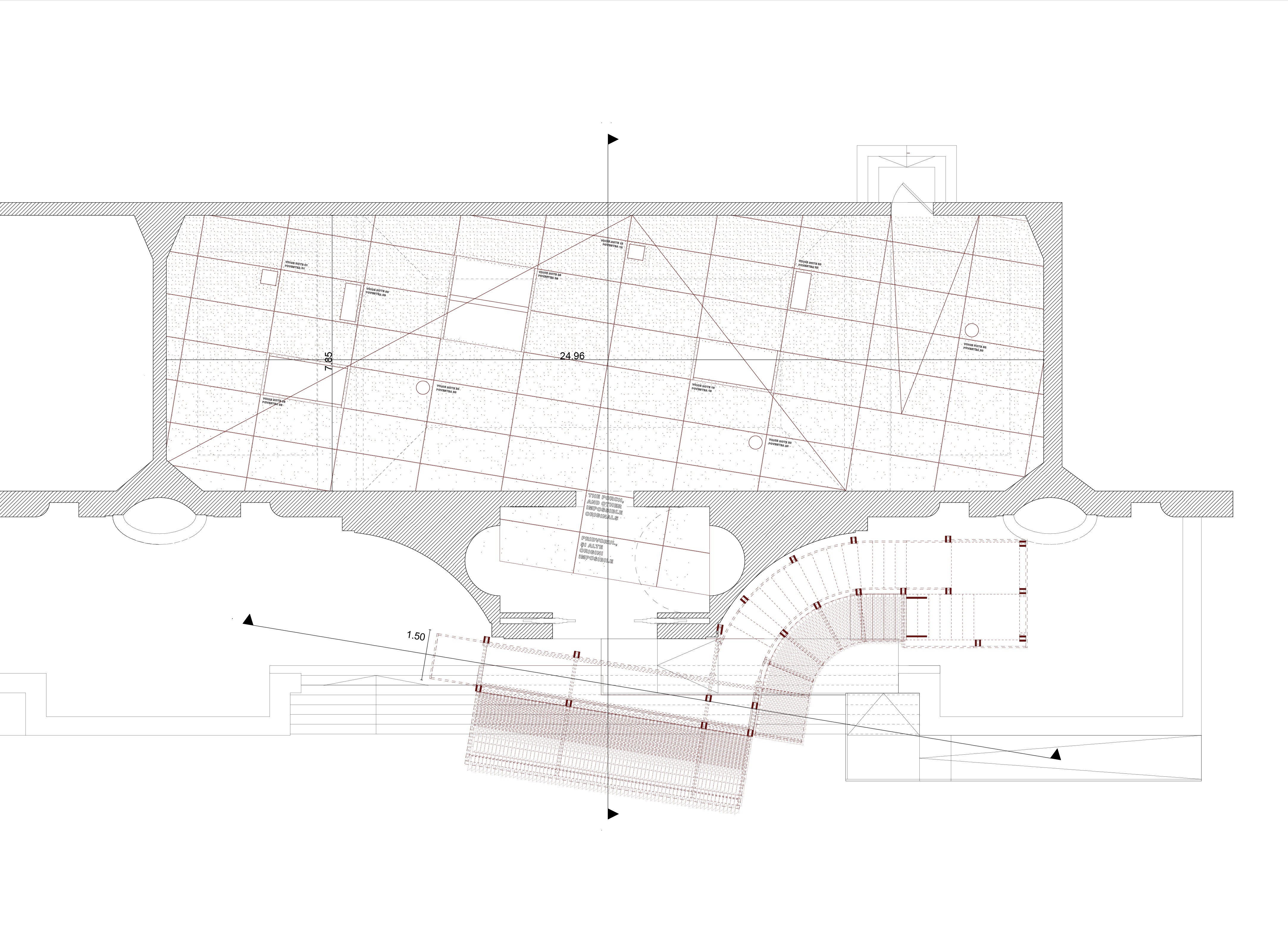

The intervention consists of two principal gestures: a transformable assemblage that engages the pavilion’s existing architecture, creating a new façade on the outside and a new floor within, both occupiable. This dual act of addition transforms the pavilion into a liminal space—partially enclosed, partially revealed. The transformability of the intervention is further emphasized by its afterlife: once the Biennale is finished, all wood material used for both elements will be dismantled and reused through a partnership with a Romanian NGO in the restoration field.

Inside the pavilion, the new floor serves as both a physical and conceptual platform. It hosts a sound installation: a collection of more than 20 anonymous recordings gathered over the spring in collaboration with Romanian cultural and educational partners. These stories, as told through the voices of a diverse group of Romanians, detail moments of architectural change and adaptation—intimate acts of negotiation between structure and life. The approach is at once indexical and deeply subjective, both spatially minimal but rich in content. The singular place of the pavilion interior thus becomes a host of many places.

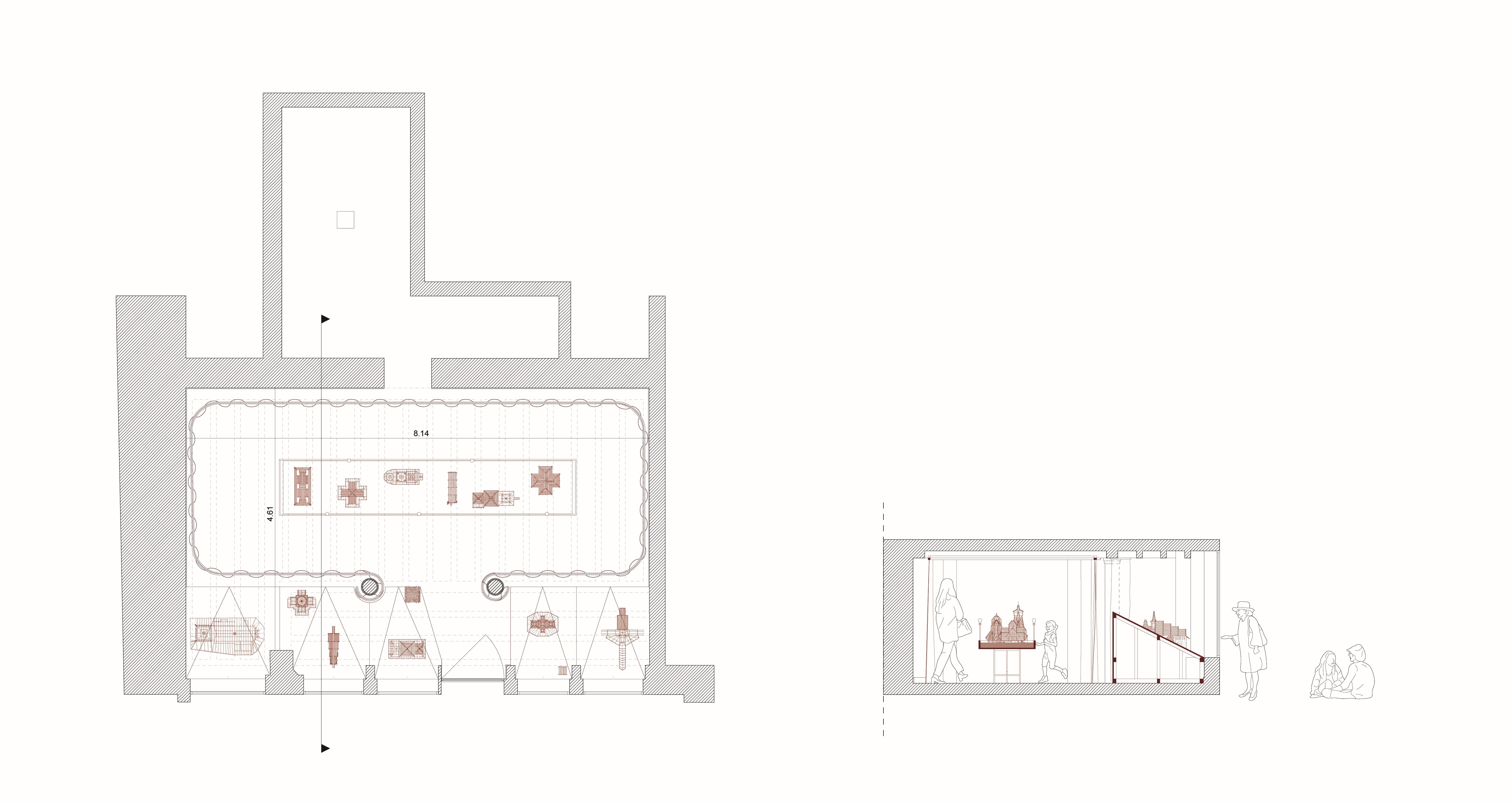

Within the ICR gallery, the themes of the pavilion are echoed and expanded. Presenting works by Romanian artists, architects, and students, the exhibition explores adaptability and transformation in Romanian vernacular architecture. Through a scenography of window displays, curtains, and tables, the gallery provides a historical and didactic counterpart to the broader themes articulated in the Giardini.

COUNTER PAVILION:

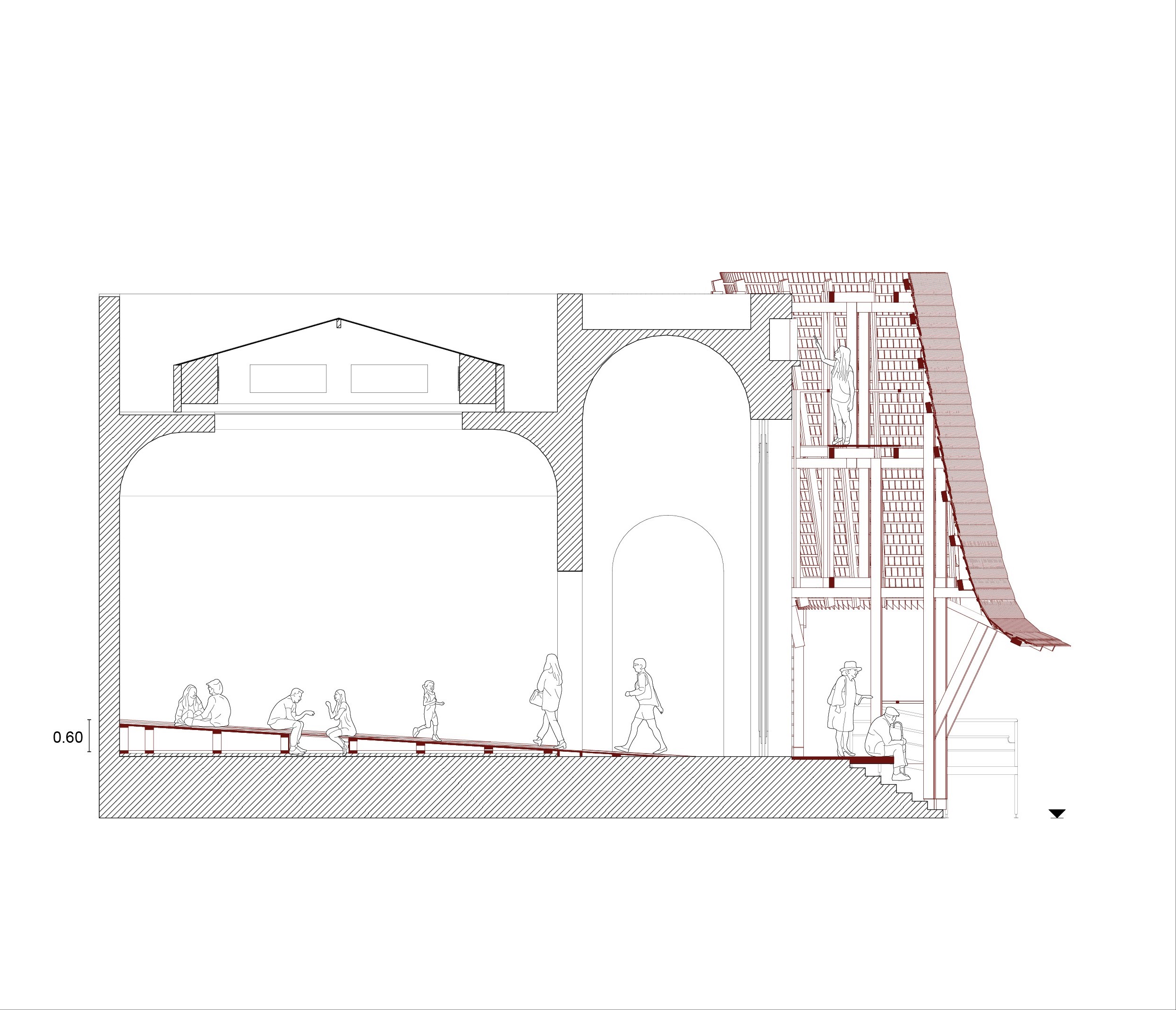

This project envisions a “counter pavilion” situated on the terrace of the Romanian Pavilion, an intervention that both inhabits and challenges this symbolic void. Constructed from a wooden assemblage, the counter pavilion offers a deliberate contradiction to the original building’s austere formalism. At its core lies the wooden shingle—a material steeped in memory, at once deeply local and imbued with transformative potential.

Central to our conceptual framework is the pridvor, the quintessential Romanian porch. This architectural form redefines the pavilion’s façade as an adaptable membrane rather than a sacrosanct boundary. In Romanian vernacular architecture, the pridvor occupies a space between the private and the public, mediating interior intimacy with exterior openness. It resists a singular purpose, accommodating circulation, rest, meals, and even sleep—a space of deliberate fuzziness, where functions coexist without resolution. The counter pavilion situates this ambiguity not merely in its program but in its material presence. The pridvor acts as a disruption to the pavilion's formal rigidity, unsettling the symmetry of the terrace and veiling its iconography. In the context of the Giardini, this intervention achieves a radical spatial reorientation: outward, it engages with the surrounding gardens and the façades of neighboring pavilions; inward, it reframes the pavilion's vacant interior as a self-reflective spectacle.

Visitors are invited to inhabit the terrace in unprecedented ways, occupying its ground level while also ascending within the new structure. This ascent provides an intimate, close-up encounter with the original façade, rendering the architecture itself an object of scrutiny. Simultaneously, the elevated vantage offers views of the Giardini landscape, intertwining the pavilion’s introspection with a new outward gaze.

VOICE NOTES:

Sound operates as a counterpoint to the visual hegemony traditionally associated with the Biennale. It subverts expectation by centering the fragmented voices of individuals, allowing no definitive narrative to emerge. The room becomes a resonant void—an instrument in itself—activated through an occupiable floor where sound emanates beneath wooden panels via directional speakers. The carefully calibrated volume ensures that narratives remain elusive unless one is in intimate proximity to the source, leaving the rest of the pavilion seemingly silent and empty. Here, absence becomes presence, as the void prompts visitors to project their own imaginings onto the interior.

By selectively opening the ground, a new spatial order emerges, inviting visitors to pause, rest, and listen to the layered stories embedded within. The apertures further articulate this experience: small openings offer solitary engagement against the ground, medium-sized ones accommodate seated reflection, and the largest create communal chambers, expanding the sonic architecture of the space. The stories they contain range from the domestic to the urban, the prosaic to the mythical. These stories challenge us to rethink the role of the asrchitect—not merely as a designer of physical objects but as a mediator of processes, an anticipator of the intelligence, irreverence, and creativity of future users. What might it mean for architecture to embrace the ingenuity, contempt, or even disregard of those who inhabit it, both near and far in time? What forms of architecture can sustain themselves in time, rather than defy it?

COMMON INTELLIGENCE:

At its core, the project explores two interwoven themes. First, it calls into question architecture’s presumed durability, challenging the modernist notion that architectural integrity is synonymous with unyielding solidity. Second, the proposal critiques the marginalization of the vernacular—so often relegated to the exotic periphery of architectural discourse as “local” or “traditional.” The vernacular carries with it a profound intelligence of place, an inherent responsiveness to its environment. Instead of attempting the futile return to some original, static state, the question arises: how do architecture and its users effect transformation over time? How might we design in anticipation of this continual flux, without falling into the trap of prescriptive solutions? These questions emerge and unfold within the context of the privdor, a space that is at once intimately familiar yet entirely foreign within the context of the Giardini. The privdor itself embodies the sempiternal—a form endemic to Romanian architecture, yet replicated and reinterpreted so thoroughly that it transcends its literal historical origins, an impossible original.